This is the first in a series of articles on America's local news crisis and the work of the newly launched Local News Initiative at Northwestern University's Medill School.

It's a jarring contradiction: The public has never had better access to news, yet local journalism is suffering a dramatic decline.

Which means there’s plenty to read and view, but it might not tell us very much.

On a single day in July, the New York Daily News cut its newsroom staff in half. The next month, Pittsburgh became the biggest American city without a daily print newspaper when the Post-Gazette went to five-days-a-week publication.

The number of U.S. newsroom jobs has dropped by about a quarter since 2008, and by 45 percent at newspapers. That has left some areas of the country virtually uncovered by journalism and plagues all news consumers with more superficiality and mistakes.

This is not just a newspaper problem. A Pew Research Center study this year found that 50 percent of people often get their news from TV – down from 57 percent in 2016. The decrease was true for local, network and cable news, but was most pronounced for local TV news.

The Internet has disrupted both the local TV news and print newspaper models, making legacy media vulnerable to takeovers by non-news-oriented companies seeking quick scores.

The Denver Post is an especially glaring example. Alarmed by draconian staff cuts ordered by hedge fund owner Alden Global Capital, the Post published a rebellious editorial in April: If Alden isn’t willing to do good journalism here, it should sell the Post to owners who will.

Chuck Plunkett, the editorial page editor who supervised the Post’s cry for help, resigned soon afterward. The Post has not been sold.

I think there's a growing consensus that the crisis in local news is the biggest crisis in American journalism today,

Tim Franklin, senior associate dean at Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications.

I think there’s a growing consensus that the crisis in local news is the biggest crisis in American journalism today,

said Tim Franklin, senior associate dean at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications. And I think it’s not just a crisis for the journalism industry. It’s also a growing problem for a self-governed democracy, because without local news, citizens don’t have access to the information they need to hold government officials accountable, to hold other institutions accountable, and to be active, engaged, voting citizens.

Franklin heads Northwestern’s new Local News Initiative, which is among several projects nationwide aimed at building audiences and making America’s newsrooms more sustainable.

Another effort is the Knight-Lenfest Newsroom Initiative, once known as Table Stakes. Launched in October 2015, it works to raise the digital IQ of major metropolitan daily newspapers. Also, the Center for Investigative Reporting recently formed Reveal Local Labs, aimed at improving investigative reporting and community input by facilitating “a spirit of collaboration” among local news outlets in four U.S. locations.

Then there’s Google, which has lured huge amounts of advertising revenue away from local news producers but is helping local newsrooms by teaming with a group of foundations to form Report for America. That project provides half the salaries for newsrooms to hire and train “emerging journalists.”

Beyond legacy media, a number of start-ups have been launched in recent years, benefitting from the relatively low cost of online-only news delivery. A group called Local Independent Online News (LION) Publishers, founded in 2012, supports such independent news organizations.

In addition, the nonprofit ProPublica has moved beyond major metropolitan areas with its Local Reporting Network, which will pay the salaries and some benefits for more than a dozen local reporters working on accountability journalism.

And then there’s an initiative that is both groundbreaking and controversial: New Jersey is spending $5 million in taxpayer dollars in an experimental program to address the local news crisis by funding community journalism.

Amid the individual efforts to make local news more sustainable, the industry may be making a broader cultural change.

Tom Rosenstiel, executive director of the American Press Institute, sees a healthy shift from chasing online page views to listening more carefully to subscribers and winning their loyalty. The notion of ‘digital first’ has given way to ‘audience first,’

he said.

This, in turn, has created greater willingness to try new things.

It’s a more alarming time than a decade ago,

he said, yet there’s more innovation, transformation and creativity than there’s ever been.

As journalism pushes forward with new ideas, it’s important to understand how the industry fell into such distress.

Cash cows wandering off

In 1997, Gannett's profit margin was nearly 30 percent. Now it's slightly over 2 percent, and has been negative in five of the last 10 quarterly reports. What happened to the journalism industry's money-printing machines?

Massive technological shifts have ravaged the business model. Subscriptions never kept newspapers going – advertising did. And the internet both undercut the value of print advertising and created a variety of inexpensive alternatives. Used to be, if you wanted to reach consumers in a small town, you needed to advertise in that town’s newspaper. Now you can buy geocoded web ads.

Advertisers aren’t civic-minded sponsors of the news. They expect a return on investment, and they’re finding other ways to get it.

A 2014 Tow Center report on “Post-Industrial Journalism” put it this way: Advertisers have never had any interest in supporting news outlets per se; the link between advertising revenue and journalists’ salaries was always a function of the publishers’ ability to extract the revenue. This worked well in the 20th century, when the media business was a seller’s market. But it does not work well today.

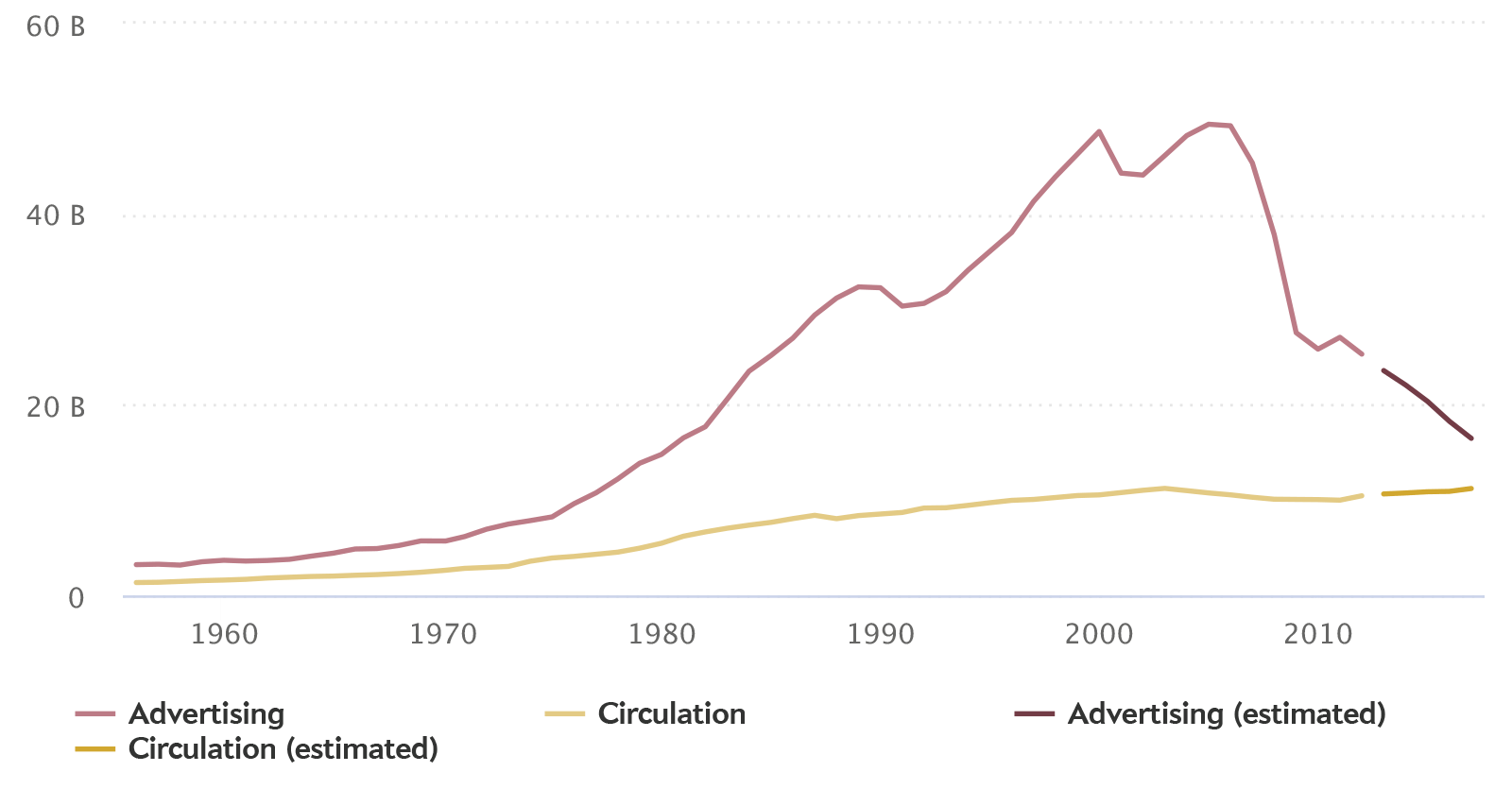

Total U.S. newspaper ad revenue reached $49 billion in 2006 and has been in a freefall since, estimated at $16 billion in 2017.

As Craiglist and other ad websites prospered, newspaper classified ad revenue plunged from $19.6 billion to $4.6 billion from 2000 to 2012.

Newspaper classified ads, historically a major cash generator for local newspapers, have shrunk in the face of Craigslist and “help wanted” sites. The big plunge came from 2000 to 2012, when newspaper classified ad revenue fell from $19.6 billion to $4.6 billion.

People still buy substantial death notices in the newspaper because the target audience is elderly readers who remain dependent on print. But even there, newspapers have lost exclusivity in the market. Many now team with legacy.com for management of their online obituary pages, with the local news organization and legacy.com splitting revenue.

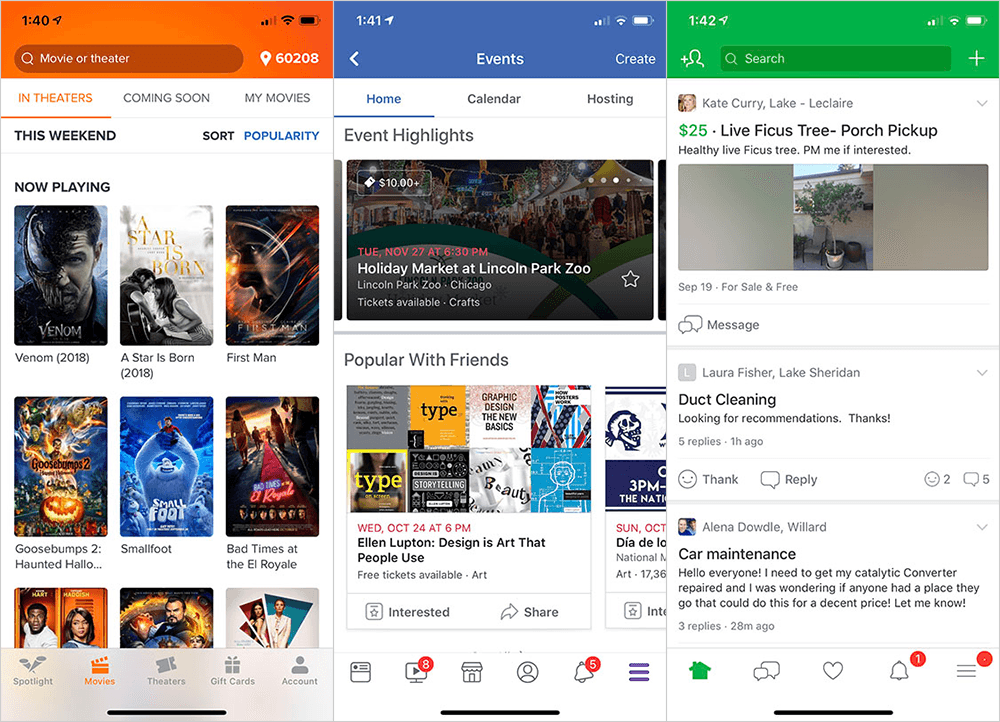

Another product that newspapers lost dominance over is calendars and event listings. Perhaps it was the lack of staff resources to keep up the lists. Perhaps it was the high cost of newsprint to publish the lists. Perhaps it was the idea that it was all available somewhere on the internet.

But for whatever reason, today’s newspapers print far fewer lists of movies, concerts, street fairs, fireworks, etc. both in print and online. These days, Facebook has become a major way that people find out about events in their neighborhood, with the added advantage of being able to tell people whether their friends are going.

Newspapers have lost primacy in many ways. Web start-ups have realized that aggregating news is far cheaper than paying expert journalists to go out and report it, then fact-check it. Sometimes the aggregators write better headlines and get more traffic than the original sources.

Vanishing news coverage

When local news staffs shrink, one result is indisputable: less local coverage.

Analyzing more than 16,000 stories from 100 U.S. communities, researchers found that only about 17 percent of the stories are actually about the municipality or take place there.

A study this year by the News Measures Research Project at Duke University found that fewer local news stories are produced than you might think. Analyzing more than 16,000 stories from 100 U.S. communities, researchers found that only about 17 percent of the stories are actually about the municipality or take place there. Just 43 percent of the stories provided by local news outlets were produced by them. And only 56 percent addressed a “critical information need”; nearly half were celebrity news and other material that many consider fluff.

Serious news requires serious news professionals – people who know how to search for records, who understand environmental regulations, who have the time and commitment to attend night meeting after night meeting to detect what’s sneaked into the budget. As news staffs shrink, reporters and editors tend to become generalists, with less deep knowledge in distinct areas and less time to do research.

Beat jobs in specialties such as religion and the environment are under pressure.

The Society of Environmental Journalists says its membership is up by 17 percent since 2002, indicating that reporting on the subject has survived the upheaval. But the number of members in certain legacy media has plummeted: Environmental writers working for newspapers are down 46 percent and those in TV have slipped 23 percent. Freelancers are up 58 percent.

The Religion News Association reports a similar trend. From 2008 to this year, its membership share from print and broadcast has gone from 87.5 percent to 42 percent. Freelancers have gone from 12.5 percent of members to 25 percent.

Penny Abernathy of the University of North Carolina has been studying “news deserts” for years, and issued an important new report on the topic this month.

Abernathy’s study defines news deserts as places without a newspaper or with “limited access” to news. There are nearly 200 counties without a newspaper and almost 1,500 counties with only one newspaper, and the punch line is that it’s usually a weekly,

said Abernathy.

There has been a net loss of almost 1,800 newspapers since 2004, including more than 60 dailies. The South has more news deserts than any other region, but it’s not just a problem in rural areas, Abernathy said. Inner-city neighborhoods and suburbs can be news deserts, too. Her study finds that California has lost the most dailies, and Illinois has lost the most weeklies.

Even the newspapers that have survived are often shadows of their former selves. Abernathy calls that “the rise of the ghost newspaper.” She cites weekly papers that have evolved into zoned sections of bigger papers and become “basically advertising supplements.”

Abernathy said big newspapers will probably survive, but she’s worried about the small and mid-sized papers. My concern is more that you’re missing the type of news that makes you informed and knowledgeable about your community,

she said.

The decline in newsroom staffing has another negative impact: Making it more difficult for news organizations to address their longstanding lack of diversity. Nearly 17 percent of U.S. newsroom employees were minorities in a 2017 ASNE survey – well below the minority percentage of 39 percent in the over-all U.S. population. Simply put, when newsrooms don’t hire, they don’t hire minority journalists.

The price of ignorance

Sometimes readers don't realize what they're not getting. But it's obvious to journalists.

There are fewer people covering the statehouses, which scares the hell out of me as a former statehouse reporter in Illinois,

said Northwestern’s Franklin. There are fewer people covering City Hall, covering local schools, covering local businesses, covering the zoning commissions, all those sorts of things. And good local reporting is expensive.

When there’s less government watchdog journalism – when the “gotcha” goes away – politicians may feel emboldened to ratchet up spending. A recent study of places where newspapers closed in 1996-2015 found that government borrowing showed significant jumps.

Research also has found that people whose areas lack news coverage are less likely to express opinions about candidates for Congress – and less likely to vote.

In these politically divisive times, with accusations of “fake news” flying back and forth, local news can provide the kind of shared facts that create a sense of community. As Washington Post columnist Margaret Sullivan wrote about her interviews of voters in Luzerne County, Pa.: “The most reasonable people I talked to, no matter whom they had voted for, were regular readers of the local papers and regular watchers of the local news.”

The most reasonable people I talked to, no matter whom they had voted for, were regular readers of the local papers and regular watchers of the local news.

Margaret Sullivan, Washington Post columnist

The lack of local news coverage might even be making us sicker. Epidemiologists rely on local stories to help them track disease outbreaks and identify epidemics early on. Local media is the bedrock of internet surveillance — the kind of work that we do in terms of scouring the web looking for early signs of something taking place in a community,

John Brownstein, chief innovation officer at Boston Children’s Hospital, told Stat.

This dependency on local journalists as first responders goes well beyond public health.

It used to be that you had these great powerful local news organizations – and we probably leaned on them too much,

said New York Times Editor Dean Baquet on David Axelrod’s “The Axe Files.”

The big national newspapers like the [Washington] Post and the Times could get a glimpse of what was going on, whether it was Pennsylvania or Montana or Louisiana, by reading those papers. … None of those institutions have the same reach they had. There are whole swaths of America that aren’t covered.

I'm not worried about coverage of the city of San Francisco, to be frank. ... I am worried about who's going to cover Newark. I am worried about who's going to cover the working-class East St. Louis.

New York Times Editor Dean Baquet

I’m not worried about coverage of the city of San Francisco, to be frank,

Baquet said, noting the city’s combination of affluent people, universities, and small start-ups. I am worried about who’s going to cover Newark. I am worried about who’s going to cover the working-class East St. Louis. I am worried about who’s going to cover the working-class suburbs of Chicago and New Orleans where there’s not going to be an economic reason to start news organizations, and I don’t know what the answer is, but I think we have to engage the question pretty forcefully right now.

Can this industry be saved?

While the financial obstacles are daunting, there are plenty of positive signs.

In general, local news has withstood the over-all assault on media credibility waged by President Donald Trump and his supporters.

The Poynter Media Trust Survey, released in August, found 76 percent of Americans have “a great deal” or “a fair amount” of trust in local television news, with local newspapers at 73 percent. For national outlets, the confidence level was lower – 55 percent for network news and 59 percent for national newspapers.

Arizona State University surveys have found that when respondents were asked for one word or phrase to associate with “news,” they said “fake.” But they responded to the phrase “local news” with more neutral words and phrases such as “my hometown,” “local station” and “local paper.”

Clearly, Americans haven't stopped caring about news. Far from it. The problem is the lack of a solid business model that would allow media companies to invest in journalism.

With advertising dollars evaporating and the industry’s obsession with online page views easing, various approaches that prioritize audience revenue have emerged.

I think this development is a really healthy one,

said Northwestern’s Franklin, because there needs to be a larger value proposition for a local news organization to get someone to pay, and it’s a proposition that isn’t based just on a sensational headline that’s going to get a ton of clicks. And it’s also a relationship that is pegged to try to make it a long-term relationship, so that people think that it’s central to their lives and that it’s a valuable experience to them.

News outlets – both legacy media and start-ups – are trying to achieve digital subscriber levels that will keep them afloat. The Philadelphia Inquirer, for example, has signed up about 25,300 digital subscribers one year into a three-year plan that has a goal of reaching 100,000. All news outlets that seek to make consumers pay for content are battling the common public expectation that news is free. But cable TV had that same challenge once and overcame it.

API’s Rosenstiel said the industry’s culture changes that are aimed at serving subscribers are reason for optimism. Local journalists are learning to listen better, and they are also embracing metrics to track audience preferences. Those metrics often endorse a news organization’s “deep sense of mission,” with high regard for investigations and enterprise, Rosenstiel said.

The thing that wins over subscribers and makes them trust and value you is what journalists have always valued,

he said.

While there is now a major push for general subscriptions, here are some other concepts for getting users to financially support news organizations:

- Micropayments, in which people would be charged a very small amount per article.

At this point I would say micropayments equal micro revenue,

Franklin said. “There’s not a lot there yet.” - Bundling, which Franklin calls “a Spotify type model for local news.” Readers would pay a modest amount per month to gain access to a variety of news sources.

That, I think, is an idea that is interesting, but it also would require … a whole bunch of publishers to sign on to that platform. And that’s where I think there could be an obstacle.

- Unbundling, in which news outlets take a segment of their content, enhance it, and sell it separately as a vertical. The Dallas Morning News is doing that with its sports content, a product called SportsDay. Three McClatchy papers – Kansas City Star, Miami Herald and Raleigh (N.C.) News & Observer – have similar offers.

I think we’re now in a world of specialization and niches,

Franklin said.

There’s no question that local news is in crisis and we’re in a perilous time,

Franklin said. But I’m not a naysayer at all. I think that we’re beginning to see pathways to a future that’s sustainable.

Do you have feedback on our stories? Do you want to share observations about the local news crisis? Can you suggest stories that we should write or topics to explore?

Find us on Twitter at @LocalNewsIni or email us at localnewsinitiative@northwestern.edu

Please sign up for our mailing list for occasional updates about the project.