- Executive Summary

- Local News Landscape

- News Deserts

- Twenty Years of Newspaper Data

- The Public Broadcasting Landscape

- Circulation and Frequency Changes

- Ownership

- Employment

- Startups and Sustainability

Executive Summary

Our first State of Local News report, published in 2016, examined the local news landscape across America over the previous 10 years, taking data from 2005 as its starting point. Now, in the project’s 10th year, we are able to look back through the past two decades and see dramatic transformations in the ecosystem of local news. Almost 40% of all local U.S. newspapers have vanished, leaving 50 million Americans with limited or no access to a reliable source of local news. This trend continues to impact the media industry and audiences nationwide. Newspapers are disappearing at the same rate as in 2024; more than 130 papers shut down in the past year alone. Newspaper employment is sliding steadily downward. And although there has been some growth in stand-alone and network digital sites, these startups remain heavily centralized in urban areas, and they have not been appearing fast enough to offset the losses elsewhere. As a result, news deserts – areas with extremely limited access to local news – continue to grow. In 2005, just over 150 counties lacked a source of local news; today, there are more than 210. Meanwhile, the journalism industry faces new and intensified challenges including: shrinking circulation and steep losses of revenue from changes to search and the adoption of AI technologies, while political attacks against public broadcasters threaten to leave large swaths of rural America without local news.

This report tracks 8,000 outlets within the American local news ecosystem. Beyond the more than 5,400 remaining newspapers, our database of local news includes close to 700 stand-alone digital sites, more than 850 network-operated digital sites, more than 650 ethnic and foreign language organizations, and more than 340 public broadcasters.

In preparing this report, we assembled and assessed data from a wide variety of sources, including industry groups, state press associations, and government statistics. As part of this process, we also manually reviewed the news outlets in our database to ensure that they consistently publish original locally-focused content that meets their community’s critical information needs. For this year’s report in particular, we significantly expanded our database of public broadcasters to include organizations beyond NPR and PBS. For more information about our research, please review our methodology.

News Deserts

Over the past two decades, the number of news desert counties – areas that lack consistent local reporting – has grown steadily. This past year was no exception: in this report, we are tracking 212 U.S. counties without any local news source, up from 206 last year. In another 1,525 counties, there is only one news source remaining, typically a weekly newspaper. Taken together, in these counties some 50 million Americans live with limited or no access to local news.

Twenty Years of Newspaper Data

In the first quarter of the 21st century, a period marked by rapid digital innovation and evolution, local newspapers and the U.S. news media industry have undergone profound shifts. Close to 3,500 newspapers have vanished, leaving one in every four Americans with limited access to a local print newspaper. These disappearances have occurred across the country but are especially pronounced in the suburbs of large cities, where hundreds of papers have merged together. The papers that remain look profoundly different than just a few decades ago, with significantly consolidated ownership and reduced print frequencies.

Public Broadcasting

In July, Republicans in the U.S. Congress voted to rescind more than $1 billion that a previous Congress had allocated to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. As a direct result, all federal funding to local NPR and PBS member stations vanished. This leaves hundreds of public media stations at risk of having to reduce or suspend operations – at a time when their services are increasingly vital to Americans with limited alternatives for local news, especially in rural areas. In this report, we track 342 public media stations across the country. Collectively, the signals from these stations reach into more than 90% of all U.S. counties, including 82% of news deserts, making them a crucial piece of information infrastructure within the local news ecosystem.

Circulation Changes

Over the past two decades, print newspaper circulation across the United States has dropped by an estimated 80 million, a loss of 70% from 2005 levels. While print readership continues to decline, online visits to news organizations have also been in freefall; in the past four years, monthly unique page views of the websites of 100 of the largest papers have decreased, on average, by more than 40%. The model of the traditional daily newspaper is transforming with all these declines: in 2025, less than a fifth of U.S. dailies are still printed and delivered seven days a week.

Employment

Employment in local news has dropped at a staggering rate since 2005, with the newspaper industry losing more than three-quarters of its jobs, and this trend has continued unabated. In the past year. Total jobs in the newspaper industry declined by 7%, and the number of journalists employed within all media categories shrunk at a similar rate. In 39 states there are fewer than 1,000 journalists remaining.

Chains and Ownership

An ownership trend that started in 2024, when a wide range of smaller papers rapidly changed hands, continued in 2025. Within the past year, almost 250 newspapers changed hands across more than 100 transactions.

Startups and Sustainability

Over the past five years, we have tracked more than 300 startups that have emerged across the country. Support for both these new startups, which have opened in almost every state, as well as existing legacy outlets has come from a surge in philanthropic investment as well as public policy initiatives. Over the past year, such efforts have boosted a wide variety of news outlets. Overall, however, philanthropic grants remain highly centralized in urban areas, and state legislation has not been widely adopted throughout the nation, leaving many outlets in more rural or less affluent areas still vulnerable.

- Executive Summary

- Local News Landscape

- News Deserts

- Twenty Years of Newspaper Data

- The Public Broadcasting Landscape

- Circulation and Frequency Changes

- Ownership

- Employment

- Startups and Sustainability

The Landscape of Local News in 2025

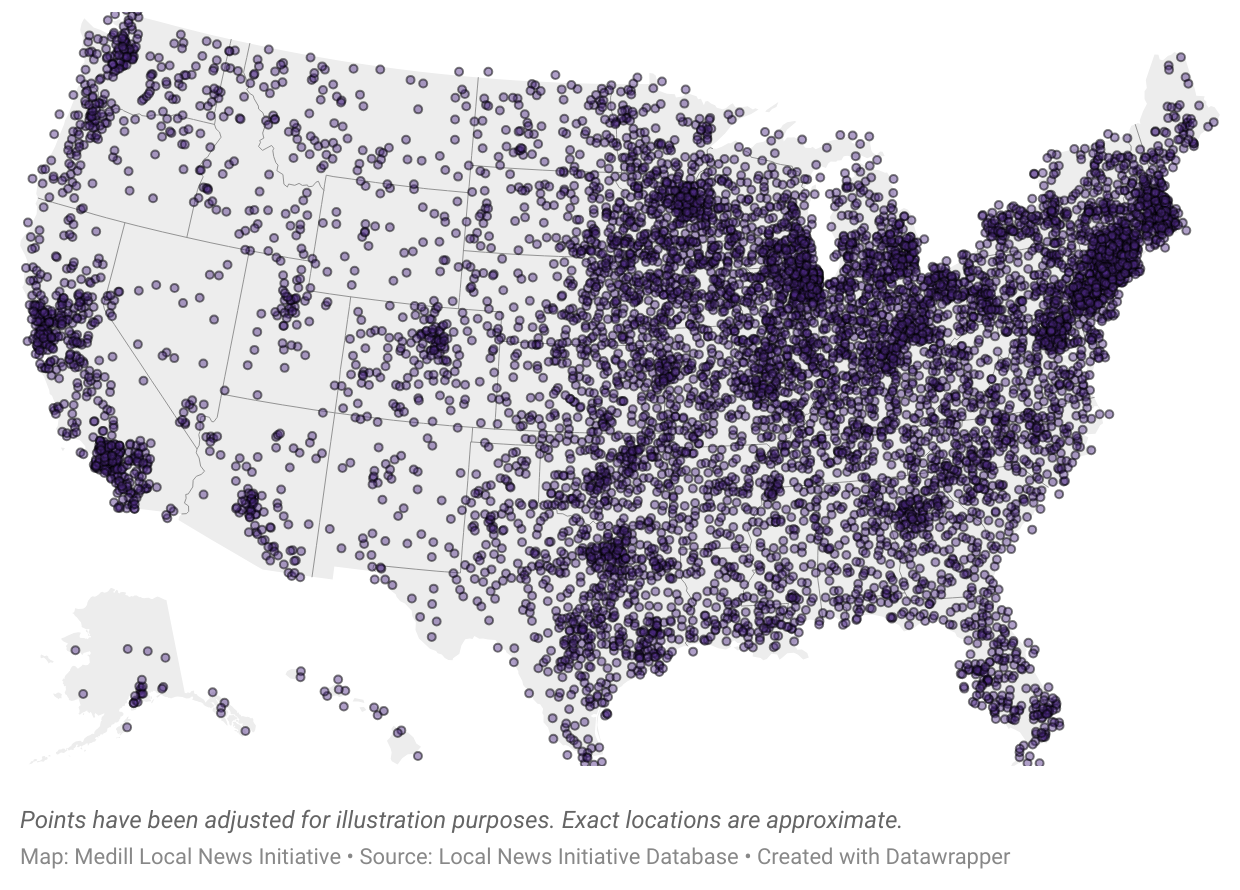

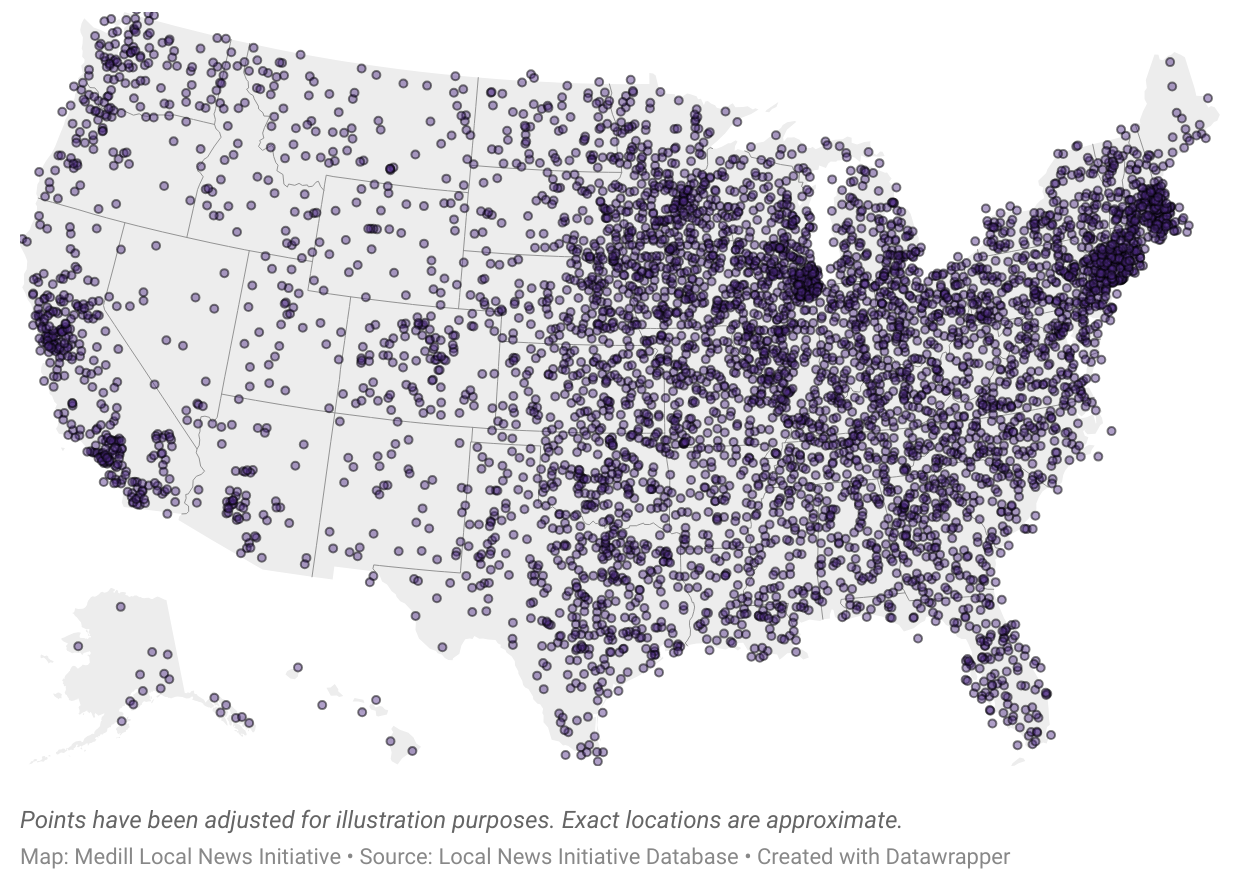

Local news in the United States is distributed widely but unevenly, closely following population centers. Of the 8,000 news outlets tracked in our database, 65% are located in urban or suburban areas.

More than two-thirds (68%) of the local news outlets in the U.S. are newspapers. The vast majority of those newspapers are weeklies, defined as being in print fewer than three days a week. Newspapers continue to disappear at an alarming rate: in the past year alone, 148 vanished due to closures or mergers, a little more than two each week. The majority of those disappearances were weeklies, but dailies were not spared – as of this year, there are fewer than 1,000 daily print newspapers remaining in the United States.

In general, these losses look different than in some previous years, when the primary drivers behind newspaper disappearances were mass closures or mergers carried out by a few large chains. In the past year, only a tenth of the newspapers that vanished had been controlled by one of the 10 largest companies. Instead, many of the papers lost in the past year were smaller, independent chains and outlets. In May, for example, four Minnesota papers closed after citing financial reasons, saying “the combined revenue for all four of our newspapers totaled less than our expenses.” In July, the Wasatch Wave, which had operated in Utah for 136 years, closed after the long-time owners retired. And in February, the Aurelia Star in Iowa shut down after the county board of supervisors voted not to carry public notices in the paper.

Even with these declines, local newspapers remain the backbone of the American media ecosystem, and are more numerous than all other media types combined. Yet for many readers, digital-only news sites are an increasingly integral part of their news consumption habits. In this update, we are tracking 695 stand-alone digital news outlets, up from 662 last year. This modest growth includes a handful of startups as well as some newspapers that have ended their print product and are pursuing a solely digital news presence.

As part of our 2024 report, we added the category of network digital sites to our database, tracking 742 individual sites across 23 network groups. This year, that number has grown to 853 sites across 52 different networks. Some of this growth has been natural: Axios, for example, expanded operations over the past year, opening new sites in cities including Pittsburgh; Huntsville, Alabama.; and Boulder, Colorado. Many other new additions to this list, however, are reclassifications from existing media categories, such as the addition of NJ.com following the New Jersey Star-Ledger’s transition to digital only publication.

As was the case last year, the number of network sites doing original reporting specific to their local community is a small fraction of the larger landscape of networks. For example, our 2025 database tracks 535 Patch sites that offer original local reporting. As a larger organization, however, Patch boasts more than 11,000 sites, a massive jump from just under 2,000 in 2024. In our review of these sites, we found that almost all of them fall into the category of Patch AM, the network’s “news brief” collection of aggregated newsletters.

While standalone and digital network sites are strong alternatives to print newspapers for many readers, they remain heavily concentrated. Less than 10% of digital-only news outlets are located in counties designated as rural by the USDA. And the demographic characteristics of counties supporting digital sites are nearly the polar opposite to news deserts: These counties tend to be more affluent, with lower rates of poverty and higher rates of educational attainment.

- Executive Summary

- Local News Landscape

- News Deserts

- Twenty Years of Newspaper Data

- The Public Broadcasting Landscape

- Circulation and Frequency Changes

- Ownership

- Employment

- Startups and Sustainability

News Deserts

Every year since we began tracking local news outlets, the number of news deserts – areas with extremely limited access to local news – has grown. The past year was no exception: there are now 212 U.S. counties with zero locally-based news sources, compared to 206 in 2024. Additionally, there are 1,525 counties with only one local news source remaining, usually a weekly newspaper. Taken together, that means that one in seven Americans, almost 50 million people, live with limited or no access to local news.

A decade ago, the expansion of news deserts was tied to mass closures and consolidations driven by “media barons.” By contrast, much of the growth in news deserts over the past year can be attributed to the closures of several smaller papers that were independently owned or were controlled by small chains. Last summer, for example, two news deserts were created in Mississippi after Buckley Newspapers closed the Jasper County News and the Smith County Reformer. At the start of this year, the 141 year old Chesterton Tribune in Porter County, Indiana ceased publication again after having been revived following a brief shuttering in 2021. And in late June, the closure of the daily Eagle Times in Sullivan County, New Hampshire, created a rare news desert in New England.

News deserts have many common characteristics. On average, they tend to be poorer counties and have smaller economic outputs than the rest of the country, with populations that are less well educated. They also tend to be more rural areas: In 2025, almost 80% of news deserts were in counties the USDA classifies as predominantly rural. These factors make it challenging to establish a viable news startup; For the people living in these counties, lack of access to local news is one of many interconnected inequalities.

As previously mentioned, digital news outlets have typically emerged in counties with very different conditions than news deserts. Underdeveloped technological infrastructure is among the latter’s challenges. In the 212 news desert counties, less than half of residents have access to the fastest speeds of terrestrial internet connectivity on average, as the latest data from the Federal Communications Commission shows. In 20% of these counties, fewer than 10% of residents can access the internet at these high speeds. The dual disparities of lack of a local news source and limited internet connectivity place residents of news deserts on the edge of a widening information divide.

The shared similarities among news deserts allowed researchers from the Medill Local News Initiative and the Spiegel Research Center to develop a predictive model that examines a county’s risk levels for losing its local news sources. This model is used to generate the Medill Local News Watch List, a set of counties that have only one source of local news and are at high risk of losing it. When we first published this model in 2023, the associated watch list focused on counties with particularly high poverty rates. As part of this year’s update, we refined our watch list methodology to more closely adhere to the underlying model. Incorporating the latest data, 249 counties have been identified by our watch list as having a greater than 40% likelihood of becoming a news desert within the next decade.

- Executive Summary

- Local News Landscape

- News Deserts

- Twenty Years of Newspaper Data

- The Public Broadcasting Landscape

- Circulation and Frequency Changes

- Ownership

- Employment

- Startups and Sustainability

Twenty Years of Newspaper Data

The U.S. newspaper ecosystem has changed significantly since 2005. Although circulation of the largest dailies had declined since the industry’s peak in the 1980s, the overall number of papers and the revenue they generated had remained relatively static coming into the new millennium. Within a few years, however, the industry’s fortunes plummeted. The print-advertisement-based business model that had sustained American newspapers for the previous century began to collapse. As more and more papers closed, the ones that remained became prime targets for consolidation by new and aggressive media chains.

Local Newspapers from 2005 to 2025

(One challenge in performing a county-level analysis is that the boundaries of counties in the U.S. have shifted in some cases over the past twenty years. Notably, in Alaska, where census areas and boroughs form county equivalents, there have been several splits among such entities, such as the city of Skagway separating from the larger Skagway-Hoonah-Angoon Census Area in 2007. For the purposes of this analysis, we are using 2010 county definitions when referring to 2005 data. The recent overhaul of Connecticut’s county boundaries does not impact these findings.)

Since 2005, close to 3,500 newspapers have ceased printing, but these disappearances have not been equally distributed. Some states have lost significantly more newspapers than others: Percentage-wise, Maryland, New Jersey, Maine, Hawaii and Ohio have lost the most. Twelve states have lost more than 100 newspapers in the past 20 years.

An examination of the counties where newspapers have vanished reveals trends in where the greatest losses have occurred. The crisis of local news is often characterized as a rural problem, but in terms of magnitude, the disappearance of local newspapers has most starkly impacted urban and suburban areas. Of the 3,500 newspapers that have vanished since 2005, almost 70% disappeared from counties categorized as predominantly urban. A quarter of newspaper losses have occurred in just 10 metropolitan areas, with New York, Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia and Minneapolis the five cities most affected. Almost a third of U.S. cities have lost more than half of their newspapers. Some have lost significantly more: Milwaukee, for example, has lost 80% of its newspapers over the past two decades, as has Rochester, New York. Columbus, Ohio, has lost 74%, with more than 45 papers vanishing.

In part, these urban losses have been greater because these areas had the most to lose. But they also speak to how newspapers have disappeared. Suburban newspapers proved particularly vulnerable to the mass consolidations carried out by large chains. Near Boston, for example, the suburban papers owned by Gannett largely have been folded into a single website named Wicked Local. In the Chicago area, the properties controlled by Hollinger International throughout Cook County largely were turned into zoned editions of the Sun-Times. And in California, many of the community weeklies surrounding Los Angeles were shut down throughout the 2010s by Freedom Communications before its sale in 2016.

Consolidation in newspaper ownership has been particularly striking. In 2005, there were 3,995 unique owners. Today, ownership has halved, with just under 1,900 owners remaining. While many of the vanished companies were smaller owners that disappeared along with their independent newspapers, the largest owners were not spared from consolidations. Indeed, several of the top owners in 2025 were formed out of mergers among the biggest chains that controlled the landscape in 2005. The two largest chains 20 years ago, Gannett and GateHouse Media, each with more than 150 papers, combined when the parent company of GateHouse -- New Media Investment Group -- bought Gannett in 2019, before adopting the Gannett name. Two other large owners, the Journal Register Company and Boston Herald parent Herald Media, were both acquired by MediaNews Group, a publisher owned by Alden Global Capital. Knight Ridder, a technology pioneer of early internet publishing, was acquired by McClatchy in 2006.

Independent ownership has also transformed. The proportion of newspapers that are independently owned has dropped especially among smaller, rural papers, declining from 54% in 2005 to 47% today. Among dailies, the differences are even more stark. In 2005, the more than 1,500 daily newspapers were owned by 459 unique owners. Today, the remaining dailies are owned by just 162. The vast majority of these dailies are controlled by larger and medium-size chains; less than 15% remain independently owned.

- Executive Summary

- Local News Landscape

- News Deserts

- Twenty Years of Newspaper Data

- The Public Broadcasting Landscape

- Circulation and Frequency Changes

- Ownership

- Employment

- Startups and Sustainability

The Public Broadcasting Landscape

The era of public broadcasting in the United States formally started almost 60 years ago. The Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 established the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) and laid the foundation for dispersing taxpayer funds to support public broadcasters nationwide. The conceptual origins of public media began much earlier, however, according to Anna Brugmann, senior manager for states policy at National Public Radio (NPR). “This is an essential promise that our government made to Americans really early on,” said Brugmann in an interview with Medill. “That they have the ability to access information that reflects their communities and share it with each other and enter into a national conversation no matter how difficult that may be. And public media is among the best suited to fulfill that role.”

The two major components of public media – NPR and the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) – were incorporated in 1970 and 1969, respectively. These organizations, along with dozens of smaller public media stations and networks, have grown to play significant roles in the broader local news ecosystem.

As part of our 2025 update, we have expanded the scope of our public broadcasting data to better reflect its place in the local news landscape. Our database tracks nearly 300 radio stations and more than 100 public television stations that originate local reporting content within their programming. Beyond these, we are also tracking hundreds of repeater and affiliate signals that broaden the geographic reach of these stations. For more information on how this update was conducted, please review our methodology.

The public broadcasting stations tracked in this update are located in 278 counties. In nine counties – six in Alaska, one in Idaho, one in New Mexico and one in South Dakota – a public broadcasting station is the sole source of local news coverage. In 47 other counties, public media is one of only two sources, with the other typically being a weekly newspaper.

Outside of newspapers, many media alternatives such as digital outlets are heavily concentrated in urban and often more affluent areas. But public broadcasting, and public radio in particular, is different. Although two-thirds of radio stations emanate from urban locations, the remainder are spread throughout the country, bringing local news to many rural regions that are otherwise underserved by local sources.

Every state has at least one public broadcaster, but the dynamics of how these are distributed differ from the distribution of other outlets in the news ecosystem. Alaska, for instance, with its low population density and vast expanses of rugged terrain, has the most public broadcasting stations of any state. It is closely followed by California, with Colorado, New York and Texas rounding out the top five.

One of the key advantages of public broadcasting that makes it a potential remedy to news deserts is that the signals from many stations reach into areas with limited access to other forms of news. In an analysis of the signal contours for each of the public radio stations in our database, Medill researchers found that the primary stations reach into 46% of news desert counties and 53% of counties with only one news source. When repeaters are included, this reach jumps dramatically, with signals extending into 82% of news deserts and 90% of single-source counties.

NPR has expanded on this infrastructure by explicitly organizing stations into regional networks that are able to share information, reporting and resources. This model allows stations to work together in times of emergencies, such as the aftermath of Hurricane Helene in western North Carolina, and to elevate more routine stories and reporting. As Brugmann puts it: “The ability to collaborate with each other as public radio stations has been a significant value proposition that we offer to the American people to facilitate local, regional and national conversations.”

Recent congressional actions have complicated this mission. The proportion of money that NPR and PBS receive from the federal government has decreased significantly since their early years, when the majority of their funding was federal . Yet cutting off federal support for public broadcasting has been an objective of conservatives for decades. This came to fruition in July, when Republicans voted to rescind more than a billion dollars that had been allocated for CBP disbursement through fiscal 2026 and 2027.

This clawback posed a sudden and significant threat to stations across the country. Although NPR and PBS receive only a small portion of their operating budgets from the federal government, individual member stations are in very different financial situations. The budgets of these stations can vary wildly, with some dependent on federal grants for a small fraction of their revenue, while others rely on federal support almost exclusively.

In a review of station finances from 2023 and 2024, we found that roughly two-thirds of stations receive more than 10% of their funding from government sources through the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. In about 10% of stations, that support counts for more than 40% of funding, putting these stations at elevated risk of having to drastically scale back operations or shut down entirely. The stations with the highest dependencies tend to be those located in poorer, more rural areas. Of the 24 counties with stations that receive more than 40% of their funding from federal sources, half are classified as very rural. These stations face a dual challenge: A large percentage of their funding has vanished, and they cannot make up the deficit through audience or local business donations, as stations in more urban areas might be able to do.

Already, federal funding cuts have taken their toll, with layoffs announced by several outlets, including PBS North Carolina and KUNC in Colorado. And while no station has closed this year as a result of the recissions, several stations face that possibility; NPR CEO Katherine Maher estimates that as many as 70 to 80 could disappear. At least one station, New Jersey PBS, has announced it will shut down next summer.

Despite all this, public broadcasting enjoys strong public support and trust, with an estimated two-thirds of Americans saying they value the local programming put out by public media stations. As Brugmann says, “In answering this question of not only how do we talk to each other, but how do we talk to ourselves and our community, public radio as an anchor and as a center of gravity is so essential for meeting the American people where they are.”

- Executive Summary

- Local News Landscape

- News Deserts

- Twenty Years of Newspaper Data

- The Public Broadcasting Landscape

- Circulation and Frequency Changes

- Ownership

- Employment

- Startups and Sustainability

Circulation and Frequency Changes

Of all the metrics used to measure the newspaper industry, readership is perhaps the one that has plummeted most. In 2005, combined newspaper circulation of dailies and weeklies hovered around 120 million. For the population at the time, that means there was one newspaper produced for every two and a half Americans. In 2025, circulation estimates are close to 38 million, or a newspaper for every nine people -- a reduction of nearly 70%.

Of course, the share of people consuming news from a print product in 2025 is decreasing. Most news consumers looking at a newspaper will visit that paper’s website for headlines and stories of the day. In a recent Medill poll of Chicago news consumers’ preferences, just 5% said they got their news from a printed newspaper “all the time,” compared to 40% who did so using a smartphone. Yet digital traffic to local news sites is experiencing a cratering similar to that of print.

In preparing this report, Medill researchers examined the web traffic to the 100 largest newspapers whose website activity was tracked by the media analytics company Comscore. We found that, on average, these papers’ monthly pageviews declined by more than 45% over the past four years. Of those 100, only 11 experienced any growth in readership over the same period.

This drop has coincided with technological changes that threaten to upend how readers interact with news sites. The widespread integration of generative AI into search engines, for example, has led to users seeing search results with headlines and content in summary form, without actually going to the underlying sources (which are pushed down further in search results). Already, this has particularly affected some of the largest revenue generators in an outlet’s portfolio, such as product reviews and “evergreen” journalism. Additionally, traditional news outlets are facing competition from new, emerging sources. In Medill’s poll of Chicago news consumers, nearly a third of respondents said that they received news from content creators.

As circulation, readership and clicks all decline, news organizations have been searching for ways to cut costs. Reducing publication frequency has been one of the more common methods; as a result, the archetypal newspaper delivered seven days a week is increasingly rare. Of the 100 largest dailies in the country, 39 print fewer than seven days a week. Across all dailies, that proportion is more than 80%. Roughly a quarter of dailies print less than four days a week.

Reduced printing schedules have naturally led to reductions in print operations. Gannett, for example, has significantly consolidated production infrastructure over the past year, closing or announcing closures in several printing plants across the country. The plants, which printed the Columbia Daily Tribune in mid-Missouri, the Rhode Island Providence Journal, the Detroit Free Press, the Arizona Republic and the Minnesota Star Tribune, as well as numerous smaller papers, collectively employed close to 600 people, roughly 9% of all production workers in the newspaper industry. As a result of these closures, many of these papers are no longer printed in the states they cover: The Providence Journal will be printed in New Jersey, for instance, and the Star Tribune will be printed in Iowa.

Beyond reductions, many newspapers have elected to end print distribution altogether. Among the most high-profile to do so this past year was the New Jersey Star-Ledger, the largest newspaper in the state when it ceased its print product in February. Along with some of its more localized associated publications, the Star-Ledger shifted to operating as a statewide digital news outlet. Another Advance Local property, the Birmingham News in Alabama, shifted to online only in 2023. Smaller papers have done the same: The 52-year-old San Diego Reader announced in February that it, too, would be online only. This trend looks likely to continue; in August, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution announced plans to end its print publication at year’s end.

- Executive Summary

- Local News Landscape

- News Deserts

- Twenty Years of Newspaper Data

- The Public Broadcasting Landscape

- Circulation and Frequency Changes

- Ownership

- Employment

- Startups and Sustainability

Ownership

In 2024, we identified a record number of newspaper transactions taking place. Within the past year, that number has dipped slightly but remains high: Over the past year, we tracked 246 papers that changed hands across 114 transactions. Like the 268 papers that changed owners last year, the majority of these transactions involved smaller and mid-size chains. The main reason for the decreased activity compared to 2024 was the reduced presence from Carpenter Media Group, whose aggressive acquisitions last year accounted for more than 100 of the ownership changes.

- Executive Summary

- Local News Landscape

- News Deserts

- Twenty Years of Newspaper Data

- The Public Broadcasting Landscape

- Circulation and Frequency Changes

- Ownership

- Employment

- Startups and Sustainability

Employment

In our previous report, we found that the number of people employed in the newspaper industry in 2023 had dipped below 100,000 for the first time. In 2024, the most recent data available from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, that number continued to shrink. Some 91,550 people were employed across all occupations within the newspaper industry, a decline of 7% from 2023. Since 2005, more than 270,000 newspaper jobs have vanished, a loss of more than 75%.

Newspaper publishers continue to suffer significantly higher losses compared to other industries. From 2023 to 2024, the newspaper industry recorded the 11th-highest loss of jobs among any industry tracked by the BLS, in terms of percentage. Over that period, almost every U.S. state lost newspaper jobs; in half of all states, there are fewer than 1,000 newspaper workers left.

Of course, local news extends beyond newspapers. Less than a third of the nearly 42,000 journalists in the United States – just 29% – are employed in the newspaper field as of 2024, though it is the largest single category. In 2005, by contrast, the newspaper industry employed 71% of all reporters.

The other major sectors for journalism jobs are digital media and broadcast reporting, each of which account for roughly a quarter of such employment. The latter category even reported some minor growth in the past year, with television broadcasters adding close to 200 journalist jobs and radio adding close to 300. These modest gains, however, were unable to match the overall losses: In the same period, newspapers lost more than 1,200 journalist jobs and digital publishers more than 1,800. All told, the journalist occupation declined by a little more than 7% from 2023 to 2024, almost identical to the decrease among newspaper publishers. Over that same time frame, journalist jobs fared worse than 85% of all occupations tracked by the BLS.

- Executive Summary

- Local News Landscape

- News Deserts

- Twenty Years of Newspaper Data

- The Public Broadcasting Landscape

- Circulation and Frequency Changes

- Ownership

- Employment

- Startups and Sustainability

Startups and Sustainability

Last year, encouraging signs emerged as philanthropic organizations and policymakers made efforts to support local news across the country. In April 2024, New York lawmakers added support for local news into the state budget. In May of the same year, Illinois passed legislation aimed at preserving local news organizations in the state.

Some of these efforts have begun to bear fruit. Encouragingly, in Illinois, the money provided under the new law – in the form of tax credits for retaining journalists – has been going to places where it was most urgently needed. Of the 120 outlets receiving funds from the plan, more than half were located outside the Chicago area. No money was directed to news outlets owned by the largest U.S. newspaper owner, Gannett, or to Chicago Tribune owner Alden.

In New York, however, the legislation has stalled, and no money has been distributed to news outlets in the state this year. Additionally, while legislation similar to that in Illinois and New York is under consideration in about ten other states, there have been some setbacks. A Local News Fellowship Program in New Mexico failed to get the required votes, and tax credit measures in Maryland and Massachusetts also failed to advance.

On the philanthropy side, Press Forward, founded to support local newsrooms, has begun distributing grants from its pooled fund. So far, more than 200 news organizations, all with budgets under $1 million, have received grants under this system. As with the credits in Illinois, the outlets receiving these grants have been in a variety of geographic locations, with a little more than half of the grants going to urban areas, and more than a quarter being directed to rural communities.

Additionally, facing the sudden loss of federal support for public broadcasting, several foundations have announced an initiative to provide emergency stopgap funding to the most vulnerable outlets. The plan aims to make $36.5 million available in stabilization grants and direct support for individual local stations. At the state level, public media organizations are also mobilizing to help disperse resources, such as New York Public Radio, which recently announced a program to make syndicated content freely available to the stations most at-risk from the loss of funds.

Despite this, the overall philanthropic landscape of journalism remains heavily centralized. In a review of the 10,000 largest journalism grants distributed over the past five years, Medill researchers found that these grants – totaling more than $1.1 billion – were allocated to just under 1,000 recipients. Furthermore, 95% of these grants, and 98% of grant dollars, went to organizations in urban areas.

Over the past five years, more than 300 new local news startups have emerged across the country. Just under 80% of these startups have been digital, either standalone or part of a larger network site, but there have also been some print newspapers established as well, such as the Grainger County Journal in Tennessee, which started in March, or the La Conner Community News in Washington state, which opened at the beginning of the year.

Smaller, independent local outlets are a key backbone of the American local news ecosystem, as they are often the most active and trustworthy sources for community audiences. These are also the outlets that have proved especially vulnerable to closures and mergers over the past year, in a departure from the corporate consolidation of years past. Supporting community local news, especially in rural areas that are often overlooked by funders, is essential to ensuring that people can continue to access reliable information and maintain a strong sense of local identity.